Microsoft Japan tested a four-day work week in August and, the company says, overall productivity increased by 40 percent.

The special program, called “Work Life Choice Challenge,” also urged staff to reduce the time they spent at meetings and responding to work emails.

The company says

it saw increased efficiency in several areas. Electricity costs dipped by 23

percent and workers printed nearly 60 percent fewer pages.

Four Days of Work Beats Five?

Microsoft gave employees who participated in the program a special paid leave, allowing them five days’ pay for working four days a week, the company says.

Because of the shorter workweek, the company also cut short meetings. The company slashed the standard duration for meetings from 60 minutes to 30 minutes, using the approach for nearly half of all meetings in August.

In a related cut, office managers held the standard attendance at those sessions to five employees.

“In the spirit of a growth mindset, we are always looking for new ways to innovate and leverage our own technology to improve the experience for our employees around the globe,” a spokesperson for the company told NPR.

“Death by Overwork”

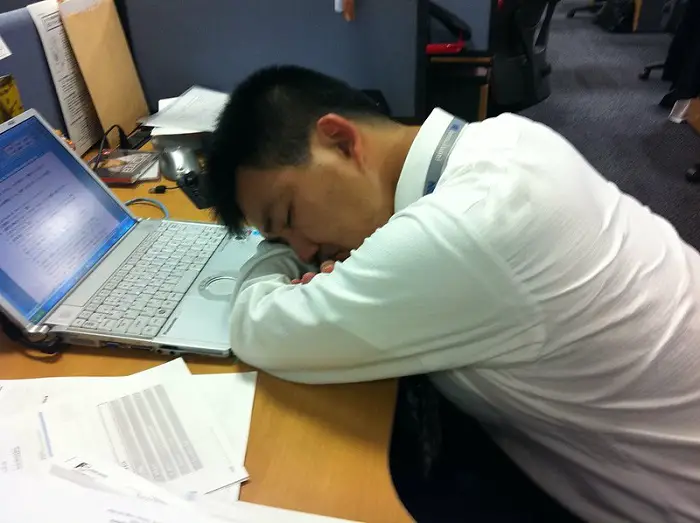

The initiative is both sensible and timely. Japan has long struggled with a grim – and all too often fatal – culture of overwork. Many Japanese employees leave for work in the morning and pass out from fatigue on their way home in the evening.

The problem is so severe, the Japanese have coined a term for it. The word karoshi means death by overwork – a legally-recognized cause of death in Japan since the 1980s.

Experts attribute karoshi fatalities to stress-induced illnesses, fatigue, or severe depression.

The issue has attracted international attention, grabbing headlines around the world. Miwa Sado, who worked at a broadcast company in Tokyo, logged 159 hours of overtime and took only two days off in the four weeks leading up to her death.

Sado died of heart failure in July 2013. She was only 31. Her employer only went public about the tragic circumstances of her death in 2017.

Two years earlier, young Matsuri Takahashi worked 105 hours of overtime in a month at the Japanese ad agency, Dentsu.

Physically and mentally shattered, Takahashi jumped off her employer’s roof on Christmas Day 2015. Tadashi Ishii, Dentsu’s president and CEO, resigned a month later.

In all, more than 2,000 Japanese employees killed themselves due to work-related stress between the years 2015 and 2016, according to the government.

Dozens of others died from strokes, heart attacks, and other health problems brought on by too much time at work.

“The Money Question”

The problem has led Japanese businesses to start searching for solutions. In fact, some companies have begun offering employees more flexibility.

For its part, the Japanese government has started “Premium Friday,” a campaign which encourages workers to leave early every last Friday of the month.

The growing enthusiasm for a four-day workweek should not be taken as proof that today’s employees simply want to avoid work, says workplace analyst and author, Dan Schawbel.

To prove his assertion, Schawbel points to what he calls “the money question” from an often-cited 2018 survey he conducted with Kronos. The question was: “If your pay is constant, how many days a week do you want to work?”

One of the potential replies to the question was simply, “None.” Only of 4 percent of the workers chose that answer. Just slightly more chose one day, or two.

By far the biggest portion – around 34 percent of those surveyed – said they want a four-day workweek.

Schwabel emphasizes the significance of the survey. “It’s important,” he says, “because it shows people want to work.”